Margaux Valengin

Sang Tu Erres

September 3 - October 3, 2020

The title of Margaux Valengin’s show, Sang Tu Erres, in the artist’s first language of French, translates toBlood You Wander. Margaux Valengin often makes use of titles and symbols to energize her paintings with meanings and alchemies that are neither easy to find nor finite in number. Adding a comma, the title could be read as both an address and an accusation—Blood, You Wander—referencing both the inescapability of violence and the challenge to fight it. Additionally, Valengin often uses images of blood and the body in her paintings to valorize emotions, which she calls “bodily thinking”; indeed, the bodies she presents here are often in a state of reflective yet urgent action. Read phonetically, the title also sounds like the French sanctuaire, or sanctuary; a reserve, refuge—a place for protection, healing and respite. With Sang Tu Erres, Valengin, like the female Surrealists before her, creates an impossible, fluid dream-scape, or sanctuary, outside of time and reality, of culture and civilization, of capitalism and patriarchy, where unlikely images and media are juxtaposed and reimagined, and where the quality of class and gender bondage can be named and located, as well as confronted, battled, overturned.

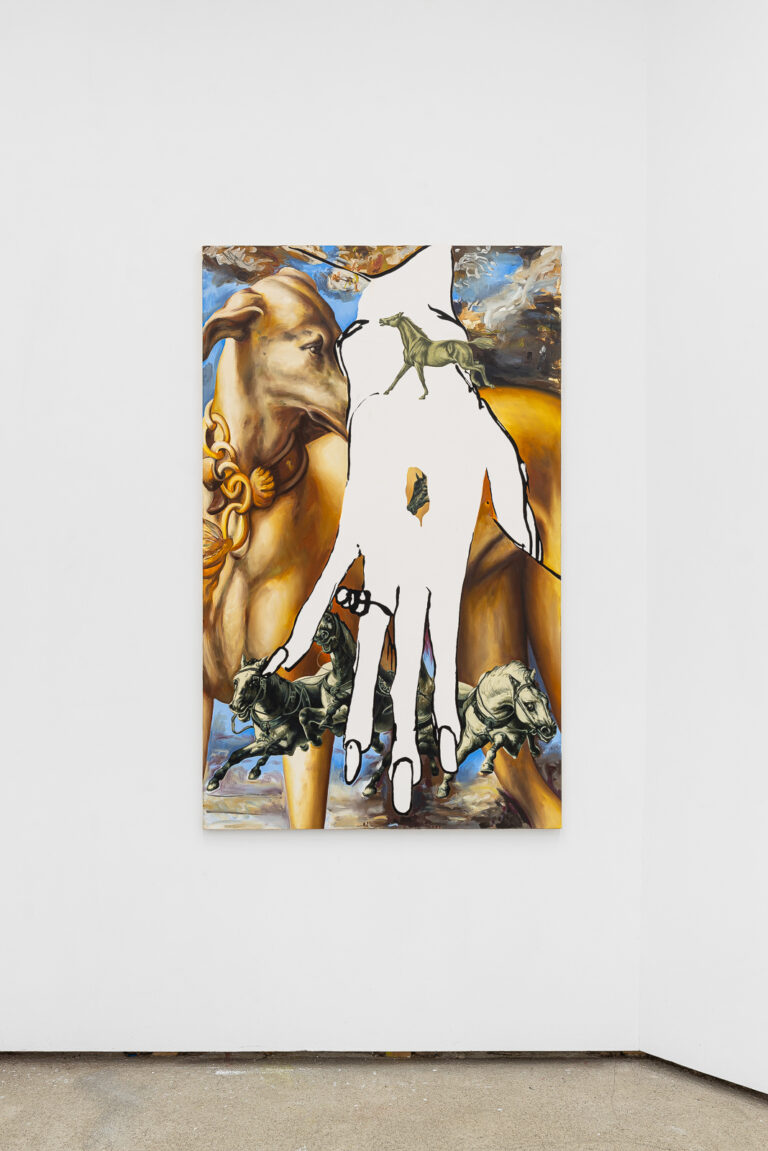

In one of the larger paintings in the show, Folle, which translates to “crazy woman”, and refers to the concept of hysteria and gendered mental illness, a trio of horses with bridles and bits in their mouths try to break free against the backdrop of what looks like a hunting dog with a chain around its neck. From the Michelangelo sky descends a witchy feminine hand, as if to disrupt this farcical “civilization”, and is printed with yet more horses, these ones wild and free. Like female Surrealist Leonora Carrington, Valengin uses horses and other organic symbols to both stand in for the vital potential of young women, and convey hostility towards the male authority and social constraints that snuff this energy out. In the painting Mors Hardcord, which translate to “horse bit” and hard “rope,” we see a pair of woman’s legs in heels and stockings, a vintage image straight out of a 1940s classic film, ensnared with ropes and an ominous horse bit. Here again, Valengin explores similar themes of female objectification and oppression, bringing together incongruent images and symbols to imagine escape.In The Newly Born Woman, named for Hélène Cixous’ book by the same name, a naked violet woman is trapped inside what could be ropes of intestines, the arterial framework of a heart, or the stifling ridges of a brain. Like all of the paintings in Sang Tu Erres, it offers multiple readings and stories. For Valengin, the possibility of many interpretations is itself an expression of resistance.

The nine paintings in Sang Tu Erresdesire away from Cartesian modes of thinking that separate the body from the mind, and towards the work of feminist-Marxist thinkers like Sylvia Federici and Cixous, who looked to women’s language and bodies as sites of profound knowledge and radical collectivity. The world of Valengin’s paintings celebrate organic forms: animals; plants; bodily organs, fluids and musculature; while also depicting the social structures that constrain them. Taken together, the surrealist montages suggest that it is within these traditionally feminine forms that our collective liberation lies, espousing the idea that Federici puts forth in Witches, Witch-Hunting, and Women: “on the meaning of witchcraft, the magic is: ‘We know that we know.’”

Svetlana Kitto // Writer (New York, Guernica, the New York Times, Interview, and BOMB) and oral historian in New York City.

Margaux Valengin manipule les titres et les symboles pour charger ses peintures de significations et d’alchimies indénombrables dont l’appréhension n’est jamais évidente. Moyennant le simple ajout d’une virgule, le titre pourrait se lire à la fois comme une adresse et comme une accusation – Sang, Tu Erres – et ferait alors allusion à l’impossibilité d’échapper à la violence tout en mettant au défi de l’affronter. Qui plus est, Margaux Valengin fait fréquemment appel aux corps et aux images de sangdans ses peintures afin de les enrichir d’émotions, ce qu’elle appelle “la pensée corporelle” et effectivement, les corps qu’elle présente ici sont volontiers contemplatifs mais curieusement sur le qui-vive. Une lecture phonétique du titre évoque également le mot “sanctuaire” ; un havre, un refuge – un lieu protégé qui offre répit et guérison. Avec Sang Tu Erres, à l’instar des femmes surréalistes qui l’ont précédée, Valengin crée un espace onirique fluide et impossible, hors du temps et de la réalité de la culture et de la civilisation, du capitalisme et du patriarcat où d’impensables images et médias sont juxtaposés et réinventés, où la servitude de classe et de genre peut tout autant être nommée et localisée que contestée, attaquée et renversée.

Dans l’un des plus grands formats de l’exposition, intitulé Folle, qui fait allusion aux concepts d’hystérie et de troubles mentaux attribués aux femmes, un trio de chevaux bridés le mors aux dents, essaie de se libérer avec pour arrière plan, un chien de chasse au cou enchaîné. D’un ciel inspiré de Michel-Ange descend une main de sorcière, comme pour déstabiliser cette “civilisation” grotesque, et sur celle-ci sont encore imprimés d’autres chevaux, ceux-là libres et sauvages. Tout comme la surréaliste Leonora Carrington, Valengin utilise les chevaux et d’autres symboles organiques pour figurer l’énergie vitale des jeunes femmes en même temps que l’hostilité à l’égard de l’autorité masculine et des contraintes sociales qui étouffent leur potentiel. Dans la peinture Mors Harcord, dont le titre joue sur une hybridation de l’anglais “hardcore” modifié pour évoquer une corde, on peut voir des jambes de femmes parées de bas et talons – image d’époque, tout droit tirée d’un film des années 1940 – prises au piège de cordes et d’un mors inquiétant. Ici encore Valengin explore les thèmes de la réification et de l’oppression des femmes en mêlant des images et des symboles discordants qui permettent d’imaginer une issue. Dans The Newly Born Woman, intitulé d’après le titre anglais du livre d’Hélène Cixous La Jeune née, une femme nue à la coloration bleuâtre est retenue dans ce qui pourraît être un entrelacs d’intestins, la structure artérielle d’un coeur, ou encore les bordures suffocantes d’un cerveau. Comme toutes les peintures de Sang Tu Erres, celle-ci offre d’innombrables opportunités de lecture et d’histoires. Pour Valengin, la possibilité de multiplier les interprétations est une expression de résistance en soi.

Les neuf peintures de Sang Tu Erres s’éloignent d’un modèle de pensée cartésien où corps et âme sont séparés, pour se rapprocher du travail de penseuses féministes marxistes telles que Sylvia Federici et Cixous qui pensent le langage et les corps des femmes comme le lieu d’un savoir profond et d’une collectivité radicale. L’univers des peintures de Valengin célèbre les formes organiques ; animaux, plantes, organes du corps, fluides et muscles, pendant qu’il dépeint les structures sociales qui les contraignent. Dans leur ensemble, les montages surréalistes suggèrent que c’est au sein même de ces formes traditionnellement féminines que se situe notre libération collective, embrassant l’idée que Federici met en avant dans Witches, Witch-Hunting, and Women: “on the meaning of witchcraft, the magic is : ‘We know that we know’.”

Svetlana Kitto // Journaliste (New York, Guernica, the New York Times, Interview, and BOMB) et oral historian basée à New York City.