Andrew Grassie, Ethan Greenbaum, Jean Nipon, Katharina Grosse, Louise Lawler, Olivier Mosset, Peter Schuyff, Richard Pettibone, Yves Klein

Entre(vues)

October 20 - November 19, 2022

The group exhibition presented by the PACT gallery stems from a deliberate choice: to show works that address the future of painting, as well as its past. There is a reflective dimension to each artist’s work that explores the materiality of the artwork itself and its principles.

Thus, if we ask ourselves about the particular question of choice in art, we realise that it definitively and fundamentally influences the way it is practised and also, undoubtedly, the way it is received. Have artists always been free?

The best conduct themselves in a way that is first and foremost true to themselves, and which is rooted in history, even if they challenge that history. What the artist needs is a vision and an idea of art that underpins their activity and production. It is a question of reflecting on art. In this respect, Marcel Duchamp was a painter and an artist who instigated an exemplary radicalism in art.

In an interview with Marcel Duchamp in 1967, Philippe Collin made a clear implication in quoting André Breton: ‘A readymade is an ordinary object elevated to the dignity of a work of art by the mere choice of an artist’. He sought to place the readymade’s creator at odds with tradition, but Marcel Duchamp, being at the very heart of contemporary art, immediately and paradoxically positioned himself within the tradition: ‘But it’s always the artist’s choice. When you make even an ordinary painting, there is always a choice: you choose your colours, you choose your canvas, you choose the subject, you choose everything. A work of art is basically a choice’. It is not opposed to history, but rather integrates itself into it, with malice and intelligence.

The artists Andrew Grassie, Ethan Greenbaum, Katharina Grosse, Jean Nipon, Louise Lawler, Olivier Mosset, Peter Schuyff, Richard Pettibone and Yves Klein encompass a broad spectrum in the field of contemporary art. They have been brought together in this exhibition with the avowed aim of producing a shock and an unusual mutual dialogue for the visitors. What can such a heterogeneous and multi-faceted vision of art produce?

Ultimately, it is the question of image that is key in this exhibition. How can we think about our bodies? Fine or coarse? Whole or partial? Abstract or figurative? Monochrome or photographic? Ordinary or intriguing? Bizarre or burlesque? Serious or critical? Hybrid or reflective? Surface or skin? How to see it? And what if, furthermore, it was multiplied?

In Ingmar Bergman’s 1966 film Persona, an utterly experimental cinematic masterpiece, the young boy, initially seen from the front, gently touches a membrane inside the image that represents the film’s canvas, which is then transformed into the image of two alternating female faces that he caresses one after the other, while we now see him from behind. At the beginning of the film, the director briefly goes through a summary of all the possible uses of filmic images. This exhibition proposes a similar discourse: thinking of the body of the painting as a film. Paul Valéry wrote: ‘the most profound thing about man is his skin’.

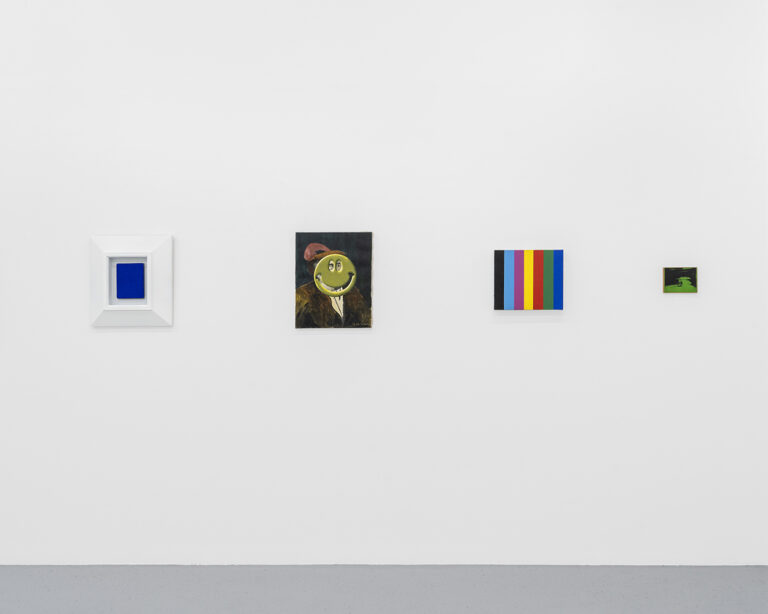

What painting celebrates, Merleau-Ponty tells us, is the enigma of vision. Between the different views offered by the exhibition, there is dialogue, discrepancy, opposition and telescoping. This is why the scenography deliberately places the pieces, all very different from one other, along a single line that can be read. The modest size of the pieces chosen allows for a linear reading of the series and requires the viewer to have a sharper eye.

This exhibition is presented as a visual alphabet that the viewer is required to decipher. Between these different views, the visitor must seek to understand a proliferation of meanings that emerge from the works and the relationships between them.

And it is no coincidence that a photograph, Ink/paint/pencil, by Louise Lawler is included in the series. It partially shows Sol LeWitt’s work in a space: two rooms photographed at ground level can be glimpsed. In her work, art becomes indexical. She captures, in an unconventional way, the place of art in its natural environment.

Olivier Mosset’s small 1988 painting from Keith Haring’s collection, measuring 35.6 x 31.1 cm, with seven unusually large vertical stripes of various colours, is a tribute to the Washington Color School, a movement founded by Morris Louis and Kenneth Noland in the 1950s, and a reminder of the Swiss artist’s connection to American painting. His work has the particularity of profoundly drawing on and dialoguing with the history of painting.

Yves Klein’s blue monochrome, IKB 275 (1960), pigment on canvas, lends colour an undeniable materiality and pre-eminence. In his painting, the colour radiates and embodies a form of concrete and porous spirituality.

Richard Pettibone’s untitled piece (1967), a silkscreen on canvas measuring 7 x 5.25 cm, appropriates Andy Warhol’s image of an electric chair by shrinking it, as the Jivaro Indians of the Amazon do with the heads of their fallen enemies. This reductive view of art is also a mise en abyme of Western culture. What is clear is that this shrinkage takes us far enough away from the artistic object to be able to grasp the cultural space to which it belongs.

In his painting Las Meninas, Diego Velázquez reduces human society to the foreground, occupying only half of the picture due to the height of the ceiling: this simple shrinking of the figures is a severe criticism of the importance attached to a person’s status in society, based on their social rank.

Jean Nipon offers a delicate and dense work made using coloured pencils. Entitled Olive Bataille (2022) and measuring 50 x 35 cm, it was created especially for this exhibition. The artist is fascinated by the masters of ancient painting, to whom he alludes in his drawings. In the portrait there is a partial reference in the background to the spears in Paolo Ucello’s The Battle of San Romano. The female comic strip character Olive appeared in 1919, later followed by a famous cartoon. Olive is courted by rivals Popeye and Brutus. The artist uses this iconic and comic image, making a portrait of it, which he associates with Italian painting.

Ethan Greenbaum’s 2019 work, Any, measuring 21,6 x 21,6 x 2 cm, is a hybrid, three-dimensional work deriving from a photograph taken by the New York artist during one of his wanderings through the city, which he transforms into a sculptural object.

Peter Schuyff’s painting Dutch Happy (2007), an oil on found canvas measuring 40 x 49.5 cm, shows the artist’s absolute freedom with respect to the subject and how it is portrayed, a huge smiley obscuring the face so only the eyes are visible, and also bears witness to his refusal to fit into one of art’s categories.

Scottish artist Andrew Grassie’s piece, entitled The Geffen (2014), made from tempera on board and measuring 12.5 x 19 cm, is based on a photograph, which serves as his model. The modesty of the work in progress that he captures, the image of a building site, is further reinforced because it is a momentarily abandoned place. The interruption of the work and the absence of human presence creates a diffuse feeling of desolation in the viewer contemplating the work. And its meticulous execution only serves to amplify this feeling.

In this exhibition, all these works, which are ensconced in an unusual and fleeting sequence, allow us to momentarily observe the life of painting and art, along with its curious projections. The world can only be glimpsed, and then we blink.

THE SYLPH

Nor seen nor known

I am the perfume

Alive, dead and gone

In the wind as it comes!

Nor seen nor known,

Genius or chance?

The moment I come

The task is done!

Nor read, nor devined?

To the keenest minds

What hints of allusions!

Nor seen nor known,

A bare breast glimpsedBetween gown and gown!

Charms, Paul Valéry

Victor Hugo Riego

L’exposition collective que propose la galerie PACT est le résultat d’un choix délibéré : il s’agit de montrer des oeuvres qui se confrontent au destin de la peinture et de son histoire. Il y a une dimension réflexive dans le travail de chaque artiste qui explore la matérialité de l’oeuvre et ses principes.

Ainsi si l’on se pose, notamment, la question du choix en art, nous savons qu’elle oriente de manière définitive et primordiale sa pratique, et sans aucun doute, aussi sa réception. L’artiste a-t-il toujours été libre?

Les meilleurs assument une conduite d’abord fidèle à eux-mêmes, et qui s’inscrit dans l’histoire, même s’ils la contestent. Ce qu’il faut à l’artiste : entrevoir une vision et une idée de l’art qui portent son action ou sa production. Il s’agit pour lui de penser l’art. À cet égard, Marcel Duchamp est un peintre et un artiste qui va instaurer dans l’art une radicalité exemplaire.

Philippe Collin, lors d’un entretien avec Marcel Duchamp en 1967, suggère clairement, en citant André Breton : » un ready-made est un objet manufacturé, promu à la dignité d’objet d’art par le seul choix de l’artiste. » Il voulait placer ainsi le créateur du ready-made dans une rupture avec la tradition, or Marcel Duchamp, étant à la source de l’art contemporain, se replace, immédiatement et paradoxalement, dans la tradition : » Mais c’est toujours le choix de l’artiste. Quand vous faites même un tableau ordinaire, il y a toujours un choix : vous choisissez vos couleurs, vous choisissez votre toile, vous choisissez le sujet, vous choisissez tout. Une œuvre d’art, c’est un choix essentiellement. » Il ne s’oppose donc pas à l’histoire mais il s’y inscrit, avec malice et intelligence.

Les artistes Andrew Grassie, Ethan Greenbaum, Jean Nipon, Louise Lawler, Olivier Mosset, Peter Schuyff, Richard Pettibone et Yves Klein incarnent un spectre large dans le champ de l’art contemporain. Ils ont été pris ensemble dans cette exposition dans le but avoué de produire un choc et un dialogue insolite entre eux pour les spectateurs. Que peut engendrer une vision si hétéroclite et multiple de l’art?

En définitive, dans cette exposition, la question de l’image est centrale. Comment peut-on penser son corps? Diaphane ou rugueux ? Entier ou partiel? Abstrait ou figuratif? Monochrome ou photographique? Ordinaire ou intrigant ? Insolite ou burlesque? Sérieux ou critique? Hybride ou miroir? Surface ou peau? Comment voir la chose? Et si, en plus, elle se démultipliait.

Dans le film Persona, de Ingmar Bergman, chef-d’œuvre expérimental absolu du cinéma, de 1966, le jeune garçon, que l’on voit d’abord de face, touche délicatement une membrane qui a l’intérieur de l’image représente la toile du film qui se transforme ensuite en l’image de deux visages féminins qui s’alternent et qu’il caresse successivement, alors qu’on le voit désormais de dos. En peu de temps, au début du film, le réalisateur passe par un condensé de tous les usages possibles des images filmiques. Cette exposition propose un discours similaire : penser le corps de la peinture comme une pellicule. Paul Valéry écrit : « ce qu’il y a de plus profond en l’homme, c’est la peau ».

Ce que la peinture célèbre, nous dit Merleau-Ponty, c’est l’énigme de la vision. Entre les différentes vues que propose l’exposition, des dialogues, des écarts, des oppositions, des télescopages ont lieu. C’est pourquoi la scénographie place volontairement les pièces qui sont très différentes entre elles sur une seule ligne que l’on peut lire. La taille modeste des pièces qui ont été choisies, permet une lecture linéaire de la série et demande au spectateur une acuité renforcée du regard.

Cette exposition se présente comme un alphabet visuel que le spectateur doit déchiffrer. Entre ces différentes vues, le visiteur doit chercher à comprendre une prolifération de sens qui émergent des œuvres et des relations entre elles.

Et ce n’est pas un hasard si une photographie, Ink/paint/pencil, de Louise Lawler fait partie de la série. Elle montre, de manière partielle, le travail de Sol LeWitt dans un lieu : on y entrevoit deux pièces photographiées à raz-du-sol. Chez elle l’art devient indiciel. Elle capte la place de l’art dans son milieu naturel de façon insolite.

Le petit tableau d’Olivier Mosset, de 35,6 x 31,1 cm, provenant de la collection de Keith Haring, qui comporte sept bandes de couleurs différentes verticales, de 1988, de taille inhabituelle, est un hommage à la Washington Color School, mouvement fondé par Morris Louis et Kenneth Noland dans les années 50, et rappelle l’attachement de l’artiste suisse à la peinture américaine. Son travail a la particularité de se nourrir et de dialoguer, en profondeur, avec l’histoire de la peinture.

Le monochrome bleu de Yves Klein, IKB 275, de 1960, pigment sur toile, donne une matérialité et une préséance incontestable à la couleur. Dans son tableau, elle irradie et incarne une forme de spiritualité concrète et poreuse.

La pièce de Richard Pettibone, sans titre, de 7 x 5,25 cm, de 1967, sérigraphie sur toile, s’approprie l’image d’une chaise électrique d’Andy Warhol en la réduisant, comme le font les indiens Jivaros d’Amazonie avec les têtes des vaincus. Cette vision réduite de l’art est aussi une mise en abîme de la culture occidentale. Il est clair que ce rétrécissement nous éloigne assez de l’objet artistique pour que l’on puisse saisir l’espace culturelle auquel il appartient.

Diego Vélasquez réduit aussi, dans son tableau les Ménines, la société humaine, à l’avant- plan, qui n’ occupe que la moitié de l’image, à cause de la hauteur du plafond : ce simple rétrécissement des personnages est une critique sévère de l’importance qu’on accorde au statut d’une personne lié à son rang social en société.

Le papier de Jean Nipon, propose une œuvre, délicate et dense, faite aux crayons de couleurs, titré Olive Bataille, de 50 x 35 cm, de 2022, et réalisée expressément pour cette exposition. L’artiste est fasciné par les maîtres de la peinture ancienne auxquels il fait allusion dans ses dessins.

Dans le portrait on aperçoit, partiellement, une référence, au fond, des lances de La bataille de San Romano de Paolo Ucello. Le personnage féminin de bande dessinée comique Olive apparaît en 1919, suivra plus tard un célèbre dessin animé. Olive est désirée par Popeye et Brutus qui sont des rivaux. L’artiste utilise son image iconique et comique, et il fait son portrait qu’il associe à la peinture italienne.

L’oeuvre d’Ethan Greenbaum, Any, de 21,6 x 21,6 x 2 cm, de 2018, est un travail hybride et tridimensionnel, issu d’une photographie prise par l’artiste new-yorkais, lors l’une de ses déambulations en ville et qu’il transforme en un objet sculptural.

La toile de Peter Schuyff, intitulée Dutch Happy, de 40 x 49,5 cm, une huile sur une toile trouvée, de 2007, témoigne de l’extrême liberté de l’artiste par rapport au sujet, à la manière de le traiter, un énorme smiley occulte le visage où seul les yeux son raccord, et du refus de l’artiste de rentrer dans une des catégories de l’art.

La pièce de Andrew Grassie, artiste écossais, titrée The Geffen, tempera sur carton, de 12,5 x 19 cm, de 2014, est tirée d’une photographie qui lui sert de modèle. La modestie de l’action en cours qu’il capture, l’image d’un chantier, est fortifiée parce qu’il s’agit d’un lieu abandonné momentanément. L’interruption du travail et l’absence de présence humaine installe un sentiment diffus de désolation chez le spectateur qui contemple l’oeuvre. Et sa minutieuse exécution amplifie ce sentiment.

Dans cette exposition, toutes ces œuvres qui sont inscrites dans une séquence, insolite et fugace, nous laissent voir, pour un instant, la vie de la peinture et de l’art, et ses étranges prolongements. Le monde se laisse seulement entrevoir, et nous clignons des yeux.

LE SYLPHE

Ni vu ni connu

Je suis le parfum

Vivant et défunt

Dans le vent venu!

Ni vu ni connu,

Hasard ou génie?

À peine venu

La tâche est finie!

Ni lu ni compris?

Au meilleurs esprits

Que d’erreurs promises!

Ni vu ni connu,

Le temps d’un sein nu

Entre deux chemises!

Charmes, Paul Valéry

Victor Hugo Riego